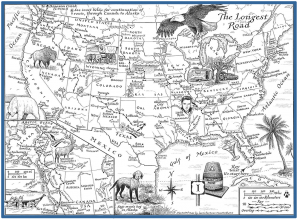

The fanciful map you see here, showing the route we followed, was created by Laura Hartman Maestro and will appear in the print and e-book editions of The Longest Road.

I love maps in all their forms: road maps, road atlases, topographic maps, marine charts. A map is the graphic representation of Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road”:

“You road I enter upon and look around, I believe you are not all that

is here.

I believe that much unseen is also here.”

A map calls you to leave the known for the unknown. It is a song in itself, promising new landscapes, new people, new experiences, and, if the traveler has a mind as open as the road before him, new insights.

A map calls you to leave the known for the unknown. It is a song in itself, promising new landscapes, new people, new experiences, and, if the traveler has a mind as open as the road before him, new insights.

My love affair with maps began a long time ago. An excerpt from The Longest Road:

“I remember an old world atlas that had belonged to my father in high school; it dated from the thirties, when some parts of the planet still appeared as white spots on the map. Oh, how I loved to stare at them and wonder, What’s there? Even in my own youth, a few places, like the depths of the Brazilian Amazon or the interior of New Guinea, remained as uncharted as Mars.”

I go on to note that today much of Mars has been mapped. As for our own planet, every square mile has been surveyed by satellite technology. There are no enticing blank spots left anywhere.

Which leads me, readers, to this observation: The benign tyranny of electronic navigation can turn an adventure into a mediocre experience, like a trip to the mall.

The risk of getting lost

If a journey is to have even an element of adventure, it also must have an element of the unknown and the unexpected. It should carry the risk of getting lost. The advent of the GPS and digitized cartography—i.e., Google Maps—have all but eliminated uncertainty from modern travel and replaced it with boring predictability.

If a journey is to have even an element of adventure, it also must have an element of the unknown and the unexpected. It should carry the risk of getting lost. The advent of the GPS and digitized cartography—i.e., Google Maps—have all but eliminated uncertainty from modern travel and replaced it with boring predictability.

We carried a hand-held GPS (a Garmin E-Trex) on the trip, as well as an Android smart-phone that, when in its GPS mode, could take us down any highway or street in America and deliver us to exact spot we wanted to reach. “Magic Droid,” as we called it, was a marvelous device, but its precision was depressing because it banished the anxiety of doubt.

Navigating with a map and compass, or with a sextant, or (most primitive of all), by the sun, stars, and terrain features, requires skill and practice. Even so, a lot of guesswork is involved, and that brings on a tingling tension, so when you arrive at your destination, you feel both relieved and gratified because your own brain and abilities, mixed with a little luck, are what got you there.

To maintain that frisson, I often artificially made things difficult. I would turn my GPS off and stash it in some hard to reach place, thus forcing myself to turn to my first love—the paper map—and then to figure out where I was and how to get where I was bound, without some gizmo doing it all for me. And when the message “No service” appeared on Magic Droid’s screen, I was thrilled.

To maintain that frisson, I often artificially made things difficult. I would turn my GPS off and stash it in some hard to reach place, thus forcing myself to turn to my first love—the paper map—and then to figure out where I was and how to get where I was bound, without some gizmo doing it all for me. And when the message “No service” appeared on Magic Droid’s screen, I was thrilled.

What do you think of all this? Are you a traveler who must know exactly where you’re going and how to get there? Or do you delight in chance and uncertainty?

I am very anxious to begin reading The Longest Road this week. I have traversed the U.S. several times beginning with my “Rte 66” like trip in November 1963 from my home in Chicago delivering a Nash Metropolitan 2-dr coupe for the owner who had moved to Half Moon Bay, CA. I had a friend with me and we

used maps extensively throughout the trip. The entire venture, with side trips, etc. is still so vivid today that

I think I could write it all in detail if I had to. My wife received a Garmin as a present and thinks it is the

greatest, as well as the built-in GPS with her newest car. I however, still like maps and will study a map before

a trip to an area new to me, so much so that I compile a memory video in mind of the route and what to expect

on the way. I was taught at an early age in Chicago by my grandfather how to get around our neighborhoods and the city by maps, landmarks and memory. During my professional life while traveling in Europe and Asia,

a colleague said the best way to learn a new city environment was to literally “get lost” and then figure out how to get to where you needed to. I believe that map reading should be a required course for 8th graders.

Interestingly, my first cross-country road trip was in 1964, when I, too, delivered a car from Chicago to San Francisco. Route 66 to the West Coast, then up 101. Does it make you you a bit fossilized, as it does me, to see that U.S.66, “The Mother Road” in Steinbeck’s words, is now a kind of open-air museum? Glad to see that you’re sticking to maps. Technology is making too many of us physically and mentally lazy.

I’ve loved maps since I was a kid, and used to spend hours poring over pages in atlases, fascinated by the colors of the topography and roads, studying places I figured I’d never get to. As an adult, I would drive my ex-wife crazy on road trips by pulling over to the side of the road and studying maps to see what was nearby or down the road.

When I discovered GPS (in a rental car picked up at the airport for a family emergency), it was an “a-ha” moment, the realization that such technology existed and worked pretty well. But it does drain the adventure out of travel. It just takes you from point A to point B, but I want to know what’s in the area, what the next road over looks like. GPS is a convenience, but I still carry a glove compartment full of maps.

My traveling companion these days prides herself on her sense of direction and considers the disembodied voice on the Droid GPS as a rival and a challenge; and there have been times when she is right and “Ms. Google Maps” is wrong.