Our 16,000-mile, four-month journey, which took us from the subtropical Florida Keys to the Arctic Ocean, and from there to the drought-ravaged plains of central Texas (where we returned our rented trailer to its owner), was more than an adventure for me: It was work.

Our 16,000-mile, four-month journey, which took us from the subtropical Florida Keys to the Arctic Ocean, and from there to the drought-ravaged plains of central Texas (where we returned our rented trailer to its owner), was more than an adventure for me: It was work.

I’d signed a contract with Henry Holt & Co. to produce a book about the trip. They’d given me an advance against expenses. I was on an assignment, a fact that rode every mile with me, causing some anxiety. What if, through some unforeseen circumstance, like illness or a serious road accident, I wasn’t able to finish the journey? Or, assuming completion, I discovered that I didn’t have enough material for a book? Or, assuming I had enough, I found that I wasn’t able to deliver the goods?

I’ve written 15 books, fiction and nonfiction, and every one has been an act of will as much as anything else.

Now, I’ll turn to what I did and how I did it, beginning with my tool kit:

MacBook Pro laptop computer. Olympus digital voice recorder. Several field notebooks. Three bound diaries. Lots of pens and pencils.

One of the purposes of the trip was to find out what the lives of Americans were like at this point in our history, a time of war abroad and recession and political divisiveness at home. I wanted to hear from them answers to two questions I’d put to myself: What holds a country as vast and diverse as the United States together? Was it holding together as well as it once did?

The art of the casual interview

The art of the casual interview

I used the Olympus to record interviews with more than 80 people from all walks of life. During the interviews, I jotted notes about their appearance, mannerisms, and important points they’d made. In a few instances, it was impractical to use the voice-recorder, so I did things the old-fashioned way – writing down what was said in a short-hand I’d developed over the years. In all cases, I tried to make these sessions as casual and conversational as possible. People are eager to tell their stories, but I’ve learned through experience that if they feel they’re being formally interviewed, they tend to become guarded, to watch their words. I wanted the people I met to speak to me as they would to a friend over coffee or lunch.

Because the Olympus’s sound quality was very poor on playback, I created an audio file on my MacBook Pro, plugged the recorder into the USB port, and uploaded the interviews. Sound quality was much improved on the laptop. I also backed up the audio files on flash drives.

Forcing myself to think before I write

There was much more to keep track of. In my field notebooks, I recorded the routes we followed and details about the towns we visited, about landscapes, weather, and the things we did, like stalking a herd of wild bison with a camera, hiking trails in the Rocky Mountains, or panning for gold in Alaska. At the end of each day’s travel, I transcribed these fragmentary notes, along with my impressions, into one of my diaries. I like writing in longhand. It seems to force me to think before I write, rather than just blurt random musings with a keyboard, knowing I can delete them with a tap on a mouse or a trackpad.

Leslie, less of a Luddite, maintained a daily blog on her laptop. After driving 300 or 400 miles, sometimes over rough roads, taking care of our two dogs, cooking and cleaning up, hitching and unhitching the trailer, etc., we would rather have had a cocktail and crawled into our sleeping bags than sit up for an hour or more, keeping our diaries and blogs current. But it had to be done.

Leslie, less of a Luddite, maintained a daily blog on her laptop. After driving 300 or 400 miles, sometimes over rough roads, taking care of our two dogs, cooking and cleaning up, hitching and unhitching the trailer, etc., we would rather have had a cocktail and crawled into our sleeping bags than sit up for an hour or more, keeping our diaries and blogs current. But it had to be done.

Following Lewis and Clark’s trail and writing discipline

Much of our route west of the Mississippi followed Lewis and Clark’s trail across the Great Plains and the Rockies. They inspired us. Trekking over what was then a pathless wilderness, in all kinds of weather, the explorers kept meticulous records, writing with quill pens in leather-bound journals. Every day for two years and four months. How meticulous? Clark, the principal navigator, calculated that the expedition had covered 4,162 miles from the mouth of the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. Modern geographers, using state of the art technology, found that he was off by a mere 40 miles.

Meriwether Lewis also had a contract to write a book about his travels. He never finished it. Fact is, he never started it. A lot of reasons have been given for that – Lewis suffered from clinical depression, for example—but I wonder if the blank page intimidated that intrepid man more than the blank country he explored.

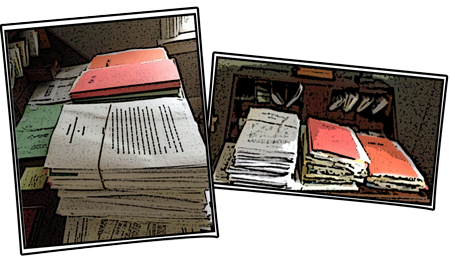

I’d begun worried that I might not have enough material. When I got home and sat down at my desk, I saw that I had too much, way too much: eighty-three recorded interviews, some up to two hours long; half a dozen field notebooks filled out cover to cover; four hundred pages of diary entries, and more than twenty file folders crammed with printed background information about the places we’d been. Plus Leslie’s blog posts, more than a hundred of them.

Writing and rewriting (and rewriting)

Making the trip was the easy part. Shaping that mountain of stuff into a coherent, informative, entertaining narrative was the hard part. The most tedious labor was listening to the interviews, some forty-odd hours worth, then taking notes on them, recording the times when someone said something worth quoting verbatim. Then came the writing and rewriting. That’s what writing is—rewriting over and over. A sentence can’t be an approximation, it must say exactly what you intended to say. Close only counts in horseshoes and hand-grenades.

Leslie’s help was invaluable—she’s a professional editor, one of the best. And my editor at Holt, Aaron Schlechter, was a master at cutting the manuscript down to size and catching grammatical errors and other mistakes.

A long time ago, when I was a cub reporter, a hard-bitten old news editor gave me this advice: Kill Your Darlings. A writer’s darlings are those verbal flourishes that he thinks are soaring examples of the prose art but are, more often than not, embarrassing examples of overwriting. I killed a lot of my darlings, but sometimes I couldn’t bring myself to plunge the knife into some glorious metaphor or paragraph. I then had to turn the assassination over to Leslie or Aaron.

“The Longest Road” underwent three complete revisions, the first draft of 500-plus manuscript pages pared down to 450, that to 350. Some chapters were revised five or six times. Altogether, writing the book took thirteen months, more than three times as long as the journey it describes.

A lot of people, maybe most people, think they can write a book. Are you one of them? If so, as much as I hate to disillusion you, I have to say that you probably can’t. But read these words and be of good cheer:

“And further, by these, my son be admonished: of making many books there is no end; and much study is a weariness of the body.” (Ecclesiastes, 12:12).

Hi Phil;

I am nearly finished with The Longest Road, and have been loving every minute of it. When my husband retired from a police department in CT, we hooked up our Argosy trailer( step-brother to your Airstream!) and took off. What memories your book brought back! We have been to 90% of the places you visited in our cross-country odyssey, and came away with many of the same impressions as you and Leslie I too have heard the battle sounds at Little BigHorn, marveled at the fierce storms across the great plains, and hate the wind towers despoiling the West.

We also traveled with a dog, a Siberian Husky, 10 years old when we started out; she explored a gold mine in SD (complete with hard-hat), flew in a small seaplane in Alaska, posed with Japanese tourists in Yellowstone, and made memories too numerous to mention.

We are fisherpeople, although not hunters, and amassed a collection of fishing licenses from various western states, and Canadian territories, and tried our luck n many of the storied trout and salmon streams.

We started out, after spending our first winter in retirement, in Florida, in April, crossing into Tok, Alaska early in June and then on to Fairbanks, which is a far as we got. After 6 weeks in Alaska, it was back across the country, and home in CT in early October.

Our journey was in 1983, and we have lived in central Oregon for 15 years now, and are still exploring

I did keep a journal of that trip, but never considered a book…………a lot of hard work there. Kudos to you for writing a great one. This is the first of your books I have read, but won;pt be the last.

I deeply appreciate your comments. Reading them, I felt that I’d like to make another journey and take more time. Fourteen weeks was too brief to cover so much territory. But I had a book deadline to meet, so maybe next time around we’ll do it just for the hell of it. Two friends of mine also visited the Little Big Horn bttlefield, and had the same eerie feeling that the ghosts were still there.

Have you visited the Alamo, Phil? It also has that feeling of being inhabited by the spirits of those who died there.

You should indeed make another journey. Still lots of country out there to explore! And maybe another book……..please.

You mentioned that you are an avid hunter and fly fisherman. Did you do any hunting or fishing on your journey? I always, following my Father’s example, carry a fly rod and some assortment of popping bugs & fly’s in my car. If I find a small bit of water I generally stop and try fishing for a bit. It makes the day perfect.

Ha! I’ll be a tease — you’ll have to read the book to find out!

This is a fantastic tutorial as well as a reality check for any writer, published or not, wannabe or not.

So glad you’ve chosen to branch out in this manner; I feel fortunate to have found you here and to receive your experience, strength, hope and doubts!

Thanks, Phil.

James Zambroski

I guess on Tuesday, we’ll find out if you got the answer to what holds the U.S. together and is that which binds us work as well as it once did.

I find your sense of insecurity fascinating..”What if..didn’t have enough material…wasn’t able to deliver…” and then later “Shaping that mountain of stuff…”

But from reading your work,watching you evolve as a writer and knowing a bit of your pedigree, those attributes and others–humility chief among them–are the stuff of greatness. You are not the type of author who believes words and circumstances are tools by which you craft a story. Such arrogance. Just the opposite is true; you surrender to the power of language and the experiences of life and people, allowing yourself to be the vehicle by which the story emerges, even as you say the acquiescence is often a struggle.

That conflict is evident here, even after 15 books; “…every one has been an act of will…” The will to be subservient and used BY language, a power which has defined human beings, is what separates great writers from the rest. You get it, Phil; maybe that comes from being shot at so many times. Something has allowed you to be right-sized when it comes to the power of words.

I loved all the stuff you spoke to concerning interviews and notes; “forcing myself to think” might be forcing yourself to be available to the writing.

I’m wondering how much of Lewis and Clark’s journals you read for research; I bet I’ll find out when Amazon delivers my copy later next week.

Good luck on Tuesday and thanks.

A friend gave me a copy of your book, Voyage a few weeks ago saying it was “right up your alley.” Larry (my husband) read it first saying, “really good. You’ll like the sailing – he’s got it right.” I just a few minutes ago finished the book (guilty at taking time out from editing a new edition of our book, Storm tactics Handbook.) Not sure if it is the close proximity of your hurricane discussion and the work I was doing, but I felt almost like I was back on board our boat during a Typhoon we weathered in the Indian Ocean several years ago. Congratulations on writing such a powerful, accurate and moving description, and also for a fine story. Too many books about the sea seem to start out right, then screw up on the details.

Sincerely,

Lin Pardey

Phil, terrific illustrations and article. Your writing…great as ever.

I always enjoy the postings on your website and facebook page.

Praying all is well with you and your family.

Greetings from the Keys!

Best always,

Suzette