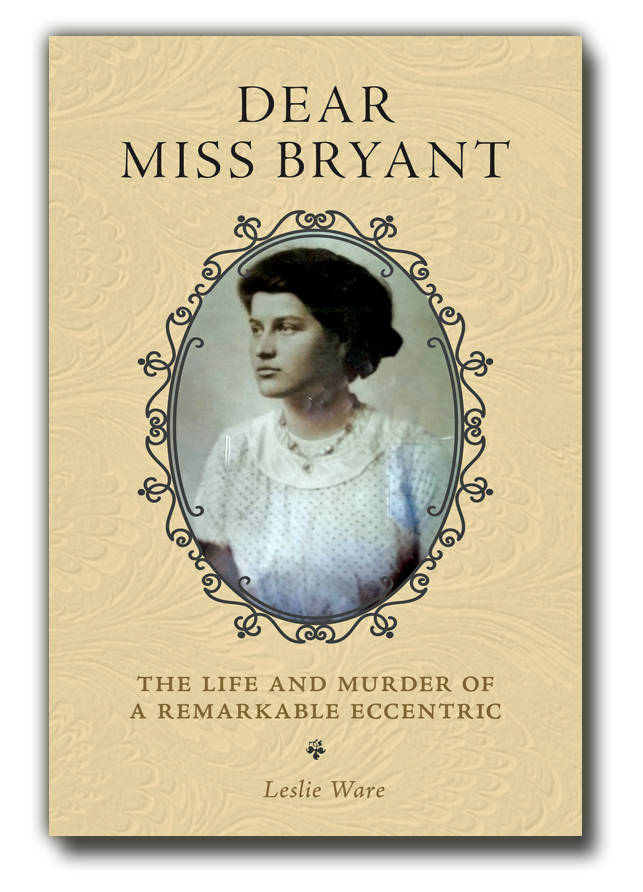

From the author of Dead Trees comes a new family memoir/murder mystery.

In 1967 Leslie Ware’s 73-year-old great aunt Julia Cox Bryant was killed in her small cottage in Durham, Connecticut. Bryant’s foster son, who lived upstairs, was charged with the murder, tried, and acquitted. For the next fifty-plus years, police forgot about the case. They reopened it in 2019, after Ware began asking questions.

Dear Miss Bryant is the story of a woman born into a life of exceptional privilege and renown who nevertheless cared nothing for money and dedicated her life to teaching others, a woman so memorable and peculiar that in the small town where she spent her adult life, she was still being celebrated five decades after her death.

She was ahead of her time, a feminist (though she would not have called herself one) who rode horseback to teach school in rural Kentucky; took foster sons on a 900-mile bicycle trip around Europe when in her sixties (they usually slept outdoors); fell in love and was jilted by an Arctic explorer; advocated for peace; and was learning new things until her dying day.

Ware weaves in quirky family traits that made Julia who she was, re-creates the accused killer’s trial, and details her quest for remaining evidence that might unravel the mystery of Julia’s death. That search led her through an array of officials until she reached three state police officers who apologized for dropping the ball for decades and began to look for answers.

AUTHOR BIO

For many years, Leslie Ware was a senior editor at Consumer Reports and Audubon. She is the author of the novel Dead Trees. In her spare time, Leslie paints landscapes and seascapes and enjoys way too many recreational activities, including sailing, tennis, biking, skiing, and rowing. She and her husband, Phil Caputo, spend summers in Connecticut and winters in Arizona.

For many years, Leslie Ware was a senior editor at Consumer Reports and Audubon. She is the author of the novel Dead Trees. In her spare time, Leslie paints landscapes and seascapes and enjoys way too many recreational activities, including sailing, tennis, biking, skiing, and rowing. She and her husband, Phil Caputo, spend summers in Connecticut and winters in Arizona.

Read an excerpt from DEAR MISS BRYANT

PROLOGUE

It was after midnight on May 21, 1967, and Great Aunt Julia was walking Cinderella down Brick Lane, the quiet strip of unlit pavement that ran by her white frame cottage in Durham, Connecticut. Julia was spry, but she may have walked more slowly than in years past—she was 73 and her black shepherd 18—and she was wrapped in a tan cloth coat to ward off the night’s chill. Intensely interested in nature, she probably admired the moon, nearly full in a clear sky; perhaps she stooped and used the flashlight she carried to peer at dandelions emerging at the roadside, or listened to the high-pitched screech of spring peepers in the swamp across from her house.

We know she had some chores “hanging over my head for immediate action,” as she put it, and she could well have been thinking about those.

Her list: “1. Weed carpet of grass off of the asparagus. 2. Cut top off tallest white pine where weevils are at work (how to reach it?) 3. Spray ground ivy—all through the hay field.” The to-dos went on through numbers 6, 7, and 8: “trim roses, finish cage, cure skins.”

Skins? In addition to a live menagerie, Great Aunt Julia kept dead animals in the freezer. At the list’s end, she wrote “etc., etc!!!!” One can only imagine what other tasks awaited.

Later that day, a Sunday, Julia was looking forward to a visit from her sister,

who was to drive the two hours from Scarsdale, New York, to Durham to see a dress Julia had bought for her upcoming 50th reunion at Vassar.

At about 1:30 a.m. a car with a young local couple and two friends drove by. Julia shined her flashlight at them; they waved in return.

She walked back to her two-story house, which was close to the street but surrounded by heavy foliage and isolated from her neighbors. Although the moon was setting, she had no need to feel around for the front door’s keyhole, as she always left the house unlocked. Once inside, she made her way past the grand piano, piles of books, and other clutter, and likely greeted the duck that had recently outgrown his carton and had begun bathing in Cinderella’s water dish, splashing its contents all over the floor.

Finally, she pulled on white flannel pajamas and a fuzzy green sweater and went to sleep in her first-floor bedroom, a wood-paneled square barely big enough for a twin bed, desk, and dresser. A few hours later an assailant crept in, threw himself on top of her, and tried to rape her, leaving a bloodstain on her thigh and smears of blood on her bedding. Later testimony

revealed that she may have cried out, “No, no!” and “Stop, stop!” The attacker then wrapped strong fingers around her neck and began to squeeze.

Julia would have felt disbelief, severe pain, then unimaginable fright. The inability to breathe is one of the most terrifying torments a human can endure. The body reacts automatically to being deprived of oxygen and blood to the brain, aware that it’s about to die if it doesn’t fight back. And so the violence escalates. Julia’s attacker, as often happens, may have thought she was dead only to find her gasping for breath. If so, she didn’t survive for long. It took him less than a minute to break her neck.

Julia’s body was discovered at 6 a.m. face down on those bloody sheets, one mottled arm flung outside the bedcovers, four gouges striping her neck. Police later found her pajama bottoms torn, rolled up, and tucked under the bed. Cinderella was licking her hand.

RECENT COMMENTS